The singer-songwriter speaks openly about the joys of feeling pain, the most consistent relationship of her life, and her bold new album, The Idler Wheel.

Tucked in the far corner of a small bar in Manhattan's SoHo Grand Hotel, Fiona Apple talks calmly and candidly about uncomfortable topics, things people are generally inclined to keep to themselves. Like whether or not she wants kids. Or past relationships. Her own dangerous birth. The limits of human empathy. Loneliness. OCD. Death. It's only when her long-time manager Andy Slater peeks in to remind her she has a photo shoot that she seems perturbed.

"I'm fine with all this stuff, until people are mean," she tells me. She continues, explaining her definition of "mean" in the context of an album's press cycle. She recalls a photo shoot for a glossy fashion magazine where she'd initially been instructed to go barefoot, until the photographers noticed her bunions. The shoot had been scheduled to run until eight p.m. "I told them, 'I'll only stay until eight if you show my feet in the magazine so that other girls can see my bunions and not feel bad about theirs,'" she says. "All of a sudden, they didn't need me until eight anymore."

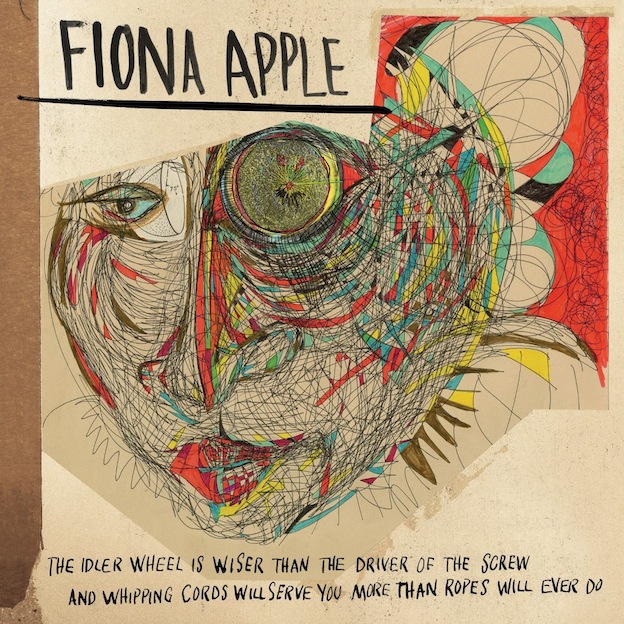

She protests when Slater tells her they need new promotional photos for her upcoming fourth album and first in seven years, The Idler Wheel is wiser than the Driver of the Screw, and Whipping Cords will serve you more than Ropes will ever do. She says she took some self-portraits for press outlets to use. I'm giddily imagining what might happen if Epic Recordswere to distribute Myspace-style cellphone shots for Fiona Apple. "Magazines need bigger pictures with higher resolutions," Slater gently informs her. "Magazines aren't that big!" Apple snaps back, exasperated.

The Idler Wheel is Apple's barest album, and its homespun instrumentation is gorgeously uneasy; clenched fists, feverish admissions, and nerve-shredding minor chords menace each warm melody. And, at 34, the singer's energy is coiled as tightly around a core of human emotion as it was during her Tidal days in the 1990s. She still seems so tethered to pure feeling that she has nothing left to expend on the practical and logistical concerns of the world around her-- driving a car, using a social media platform, taking a photo for a magazine spread. It's nearly impossible to imagine her checking her email or sorting out a calendar. Perhaps that's why her comeback is so exhilarating-- she's giving listeners a much-needed jolt from desensitizing technology and infinite fragmentation. She's always of the moment because she can't step outside of it.

Pitchfork: There are a lot of allusions to childhood on the new record. You sing, "We're eight years old playing hooky" and "I might need a chaperone." Is that an easy place for you to go?

Fiona Apple: I have a thing with wanting to get back to childhood. Right before I made the album, I would get depressed thinking about when I was a kid. I used to love to make things-- you couldn't drag me away for dinner because I was always writing a story or something.

I've always said I don't want to have kids. But up in my hotel room right now, the books I have with me are parenting books-- I had one about facial expressions and what they mean with babies that I gave to [ex-boyfriend] David Blaine's wife Alizee. This book I have upstairs is called Raising Happiness. I don't want a kid at all, but I do like reverse-engineering myself; managing and parenting myself.

Pitchfork: Have those books brought you any revelations about your own childhood?

FA: Yeah. I might sound crazy about this but, years ago, my mom told me: "We almost died when you were born. Both of us." Two weeks before I was due, she and my father were fighting on the phone. He was in Boston, and they weren't very happy with each other. She told me: "I was rearranging furniture and I wanted him to be there so he could help me push the couch. I was just so mad, so I pushed it myself and felt something strange. I was kind of in pain for a couple of weeks." Her peritoneum-- which is the film that holds all of your organs together-- had ripped, just a little bit.

I was a Caesarean baby, and the doctor who delivered me later told me, "I opened your mother up, and you were right there. It freaked me out because everything was broken and out-there." I've thought about it a lot-- could this have something to do with the fact that I'm only happy when I'm at home and alone? Maybe I was just freaking out for two weeks before I was born, feeling really insecure. I used to get a shiver if I thought about holding balloons, because I was scared of floating away. Maybe that's ridiculous, but it's something I've thought about while reading these books.

Another thing about kids: Years ago, I was thinking about whether or not I wanted to have any. I wondered if I actually didn't want to, or if I just worried that I wouldn't be able to put their problems in front of mine. So I volunteered at UCLA's occupational therapy ward, where there are lots of kids with autism and OCD and emotional problems. I went there so I could be around a bunch of kids who would say things that hurt my feelings. I just wanted to prove to myself that I could not break down and cry at everything, and that I could just help somebody else. The one thing I really remember was that when we would take them out of the hospital for a walk around campus, they would freak out the most when we were waiting for the elevator. I remember the guy at the elevator said to himself, "Transitions are the hardest." And I said to myself, "Transitions are always the hardest."

Fiona Apple: "Every Single Night" (via SoundCloud)

Pitchfork: Have you been especially reclusive since you put out Extraordinary Machine seven years ago?

FA: I'd say that I've been reclusive the last 34 years. That was my big thing as a kid, staying home from school. I've trained myself to be psychosomatically sick a lot. To this day, if I go to [L.A. club] Largo-- which is a very comfortable place for me-- I tell my brother, "I have show stomach," which feels like the flu. Anytime I go out, it is just something to deal with, even walking to the grocery store. If I'm supposed to go from one place to another place that isn't that comfortable, I usually don't go.

Pitchfork: Do you go anywhere at all?

FA: I still don't know how to drive. I don't go anywhere, really, except for Largo. My brother drives me. I walk around my neighborhood but I don't go anywhere, nor do I want to. I want to move back to the East Coast. I like Venice, but L.A. is ugly. I would kill myself if I had to look out the window and see some places in L.A. every day.

Pitchfork: What's kept you there for so long?

FA: It's my dog, Janet, who's 13 now. She's pretty sick and she's going to die soon. She had Addison's Disease and it's very dangerous so I don't want to move her; she's never had to ask to go out to pee in Los Angeles because there's always been a backyard and a dog door. This is going to sound morbid, but-- when I'm not with her, I pretend she is already dead. I can't take her on the road and I'm pretty sad about it. She is the most consistent relationship of my life and I will keep her around forever. But I like this idea of pretending that she is dead so that, when she's actually dead, I can pretend she's in another room. Just blur the line. I'm kind of waiting for her to die.

It's weird not having companionship and not having somebody to talk to. Right now, I have two goldfish in my hotel room. They said, "If you would like companionship, we can bring you a goldfish." I was like, "Bring me a goldfish!" I have two because when I needed the water changed they brought another one. I was like, "Don't take Desmond!"

Pitchfork: You named it Desmond?

FA: I don't know why. The new one doesn't have a name, but Desmond wasn't going anywhere. So now I have two. They're great. They come to the end of the bowl when I put my face there, like they are kissing me.

Pitchfork: At this point, you're 34 and onstage you're singing some very intense songs you wrote when you were a teenager or in your early 20s. Do they still resonate with you?

FA: It occurred to me when I was making this album that I fucked myself by writing all those songs when I was angry and hurt. Now, in order to live, I must rehash these memories all the time. Once the song starts, it's as though you have gotten drunk and you can't help it. The room just starts spinning. But you wake up later and you're fine; when I come out of the song, I'm out of it.

Pitchfork: How has it been singing live in front of your fans again? Being in the audience, I've been amazed by how emotional the crowds are.

FA: Now, at my lowest moments, I think of people who come to shows. I still get very sad and sometimes I feel like I have no friends, but when that happens now, I'll think of people whose names or faces I don't know-- they're my friends and they love me. I've got them. It really does save me. I still feel awkward, but that's the one thing I can grab onto at my lowest points.

I think I'm better at live shows than I used to be because I'm way more comfortable with the uncomfortable pauses between songs. Now, rather than trying to talk or do a costume change, I'll use those moments for myself. I listen to what other people are playing, or just rest, or dance, even though I don't know how to. I'm very happy that I don't get embarrassed onstage as much anymore. But I do in real life, a lot.

Pitchfork: What do you get embarrassed about?

FA: Oh, everything I do and say, really. For many years, I was a really heavy drinker, but people don't know about that because I'm by myself all the time. Recently, I didn't drink for eight or nine months, and I learned that alcohol was quadrupling the embarrassing moments-- those moments when you're drunk and you say something you remember the next morning and feel embarrassed about. I'll have a drink now, though.

Recently, I did a Watkins Family Hour show at Largo and I was getting ready to do a song. I was looking forward to getting out the emotion, it was very serious. And I didn't realize that the wonderful Paul F. Tompkins would be hosting and doing comedy between songs. He came up and started to try to joke around with me, and I said, "I don't do that," which sounds so bitchy. But it just came out. I meant to say, "I don't know how to do that and I didn't know we were going to be funny." And that just hurt for weeks because I felt rude. It doesn't sound like much, but I felt so embarrassed.

Pitchfork: I often think about something you said in an interview years ago: "Everything that happens to me, I experience it really intensely. I feel it very deeply." You've spoken a lot about honoring a spectrum of feelings. Do you still feel that way or have you hardened at all?

FA: I have gone back and forth and I have saved myself from the hardening. There is a song on the new album, "Left Alone", where I say, "I don't cry when I'm sad anymore." There was a period of time when I was not feeling things. It was terrible. Sometimes it's good to grow a tough hide-- for press stuff, maybe. But when I hear people say that they won't get a dog because they had one when they were a kid and it died, or that they don't want to fall in love because it hurts too much, I'm like, "fuck you."

I really believe in completely being naive and having high hopes when meeting someone new. I can kind of re-do my stupidity or my naivete. It pisses me off to think that we're conditioned to push away bad feelings and to think that anything that's uncomfortable is something to be avoided. When things are really bad nowadays, I recognize the value in it because it's me filling my quota-- it's going to make my joy more intense later.

The worst pain in the world is shame. I spend a lot of time trying to not do anything bad to anyone, but you can't live your life and not hurt people. Pretty recently, I did something that I'm really not proud of, and it shocked me. I thought, "I'm a really fucking bad person." But I realized that something good came out of it because now I have to be a lot less judgmental of others. Everything can make you a more compassionate person if you use it that way.

Pitchfork: What was the catalyst for this record? Was it an internal thing where you needed catharsis, or was there someone urging you?

FA: No one was urging me. Other people might be angry that their record company didn't give a shit about whether they had a record out, but I am very happy Epic didn't because that would have just made me go away and not want to do any of it. If people were like, "You gotta come out with something," it'd be like telling me to take a shit. Even if you tell me to, I can't.

Pitchfork: So what you're saying is that your music is shit.

FA: That's my metaphor for the day. This is the stuff that I really needed to get out, this is the excrement of my life, the excrement I was trying to exorcise out of me.

I'll admit that there's one song on the album that I wrote in a rush because someone made fun of me for not writing. One of my friends said to me, "Oh yeah, of course you aren't writing." So I was like, "The next time you see me, I'm gonna have a new song." I wrote "Criminal" in 45 minutes when everyone else went to lunch because I had to have a hit. I can force myself to do the work, but only if someone is right up behind me.

Pitchfork: There's a lot of unorthodox instrumentation on this new album-- quirky percussion, sampling. What took you in that direction?

FA: On the first night of recording with [producer/percussionist] Charley [Drayton], we walked by this bottle-making factory. The door was open and you could hear a machine running. We both had our recorders with us and we agreed that the sound would be good for the song "Jonathan". Juan, the guy working the night shift at the factory, let us walk through and record the sound of the machine.

That was the moment where I said, "Oh, we're not making demos-- this is going to be it. Me and Charley are going to make a record right now." And then it just got fun. On "Anything We Want", I've been playing this stupid pipe thing live, but that sound was actually me at my desk with a pair of scissors, a tin full of burnt-cedar sashays, and a plastic cup. I was hitting everything with scissors and the cedar was flying all over the place.

I've been in the business for so long, and my favorite thing is drums. I have a very, very big memory-- and I don't have many big memories-- of going to see the movie Tap, with Gregory Hines. During one scene, he's in jail, and there's some water dripping down, and he starts tap dancing. I just like that feeling of: "I'm in charge, I can do whatever I want."

Pitchfork: What about the sound of children screaming on "Werewolf"-- it seems to come out of nowhere.

FA: I wrote that song while staying at my mother's apartment up in Harlem. Whenever there's a TV, I put on [Turner Classic Movies]-- I always have it on, while I sleep, whatever. I was recording myself doing the song for the first time, and a battle broke out in the movie that was playing. People were shooting and screaming. I liked it, but I couldn't use it from the movie, so I spent literally the next year trying to recreate that sound. I went to San Francisco for Halloween and I was hanging out in trollies recording people screaming. I would walk past a bunch of drunk people and be like: "Hey, scream!" But it would always sound wrong and stupid.

But on the first morning we were planning to record, I had just gotten out of the shower and I heard all these kids screaming-- there's an elementary school across from my house in L.A. I was like, "Oh shit, that's it." I threw on whatever was right there-- which I didn't realize at the time was a pair of pants that I was going to throw away because the ass was split-- and I ran out, half-clothed, carrying my recording thing. I was standing there looking like a crazy person, watching these kids. They were jumping with balloons between their legs, trying to make them pop. In the actual song, we had to take out all the balloon pops because they sounded like gunshots. But it was so perfect.

P: Can you talk about the meaning of the new album's title: The Idler Wheel is wiser than the Driver of the Screw, and Whipping Cords will serve you more than Ropes will ever do? It's no When the Pawn... but it's still a mouthful.

FA: I came up with it in a total rush. After having stayed up all night on deadline, it just came to me right after the sun rose. I didn't realize people would be like, "Oh shit, another poem." It just came out to be what it was-- sorry.

If you think about it, the driver of the screw has one job and he is always trying to change things. But the idler wheel is there and has this great effect on what the gears do; the idler wheel knows the machine much better than just this one thing that's performing this one task.

For the second line, I had read about whipping cords in a nautical book that my last boyfriend had. I read that when ropes get frayed at sea, you can repair the frayed ends of the ropes with whipping cords that are very strong. This goes right back to the parenting thing-- if I had a kid, and I had a choice between teaching somebody how to avoid trouble, or teaching them how to get out of it, I'd teach them how to get out of it.

Pitchfork: You've never used a boyfriend's name before, but you have one song called "Jonathan" on this album. I assume that's about Jonathan Ames.

FA: Yeah, because he's a good guy. I did it because-- and I'm saying this in the most affectionate way-- he loves attention. I had come to New York for three months to write and to take a visual perception class at the New School. I was at the piano and I started writing a musical piece that reminded me of Jonathan because he is so extreme in some ways. He is just so hilariously quiet on a day-to-day basis, but when he's on stage or excited with a group of people, he's just embarrassingly bombastic. So I was like, "Hey, I'm writing this music and it reminds me of you," and he was like, "Does it have my name in it?" I thought, "I'll do that for him." But then we broke up.

One day he took me to Coney Island, where he takes all his girls. We were on the subway and-- he didn't know it at the time because we had just met-- but I had been thinking about dying a lot. I would never kill myself, but you can kind of let yourself die. But I had this good day with Jonathan; he is a very understanding person. Very non-judgemental, very kind. You can say anything or do anything and he's never going to snap at you. If I was being an asshole and he called me out on it, I would start smiling like, "Good! I am being an asshole." The song is a testament to the power of Jonathan Ames' kindness.

Pitchfork: I'm curious about your relationship with the internet. It's really hard to picture you even going on a computer.

FA: Lately, I can spend a lot of time on the internet as a substitute for TV. This is part of the reason why I'm not a good girlfriend-- you can't sit down with me and watch a movie. I hate being strapped down to stay with something. So when I watch TV, and TCM isn't on, I just switch channels and look at all the information about everything. The internet is perfect for that, which is why I didn't really want to get a computer in the first place. I thought, "If I have a computer and know about this whole Google thing, I am not going to be able to sit still for a second; I'm going to think about something and then have to look it up." I have never bought myself a computer or a phone, but guys in my life have bought them for me, for whatever reason. So now I have them.

Pitchfork: What do you do when you're online?

FA: I like slideshows. The New York Times has slideshows, and that's where I might start. Then I'll look at anything, crap. Even red carpet shit where I don't even know who any of the people are. Recently, I was looking at a "most fashionable" slideshow for some sort of kids' awards show. I did not know who any of the people were, but they were a big deal.

P: Are there any contemporary artists right now whose career you are following or whose music you are listening to?

FA: I just don't really listen to music. I'm probably missing out, but I don't want to know what everybody else is doing. Nobody is strong enough to not be influenced. And I don't mean influenced by copying-- I'd be influenced because I wouldn't want to do what someone else is doing. I want to be able to do whatever I feel like doing and not worry about anything. Even when I was a kid, the only contemporary artist I listened to was Cyndi Lauper. Everything else was Harry Belafonte and Carmen Miranda.

Pitchfork: With your comeback and the outpouring of excitement over Idler Wheel, fan camps have become territorial-- arguments over who's liked you longer or more genuinely. Are you aware of the mainstream vs. indie divide in contemporary music?

FA: I don't even know how to register that concept. How do you fight about that? That sounds like the Munchkins are fighting with the Lemon Drops about who gets to go on the candy bridge. It's imaginary. Why can't I be myself? I'll get so pissy when people describe music like, "It's like this meets this." Fucking hate that shit.

When I came in from Paris recently, for some reason the guy from customs wanted to know what kind of music I wrote. I was like, "I really want to please you so you don't keep me here, but I have no answer to that." I don't want to be one of those people who claim to hate labels, but it's true. I even feel that we've got it all wrong with the whole gay/straight thing. There is a spectrum. Everybody is completely different. Some people are way over on this side of the spectrum, some are on the other side, and some are crossed in certain ways. John is John. Joey is Joey.

Pitchfork: Maybe that's why you still resonate with people so much. Everything's become so over-classified, but you genuinely seem to exist outside of it all.

FA: I will take that as a compliment and I will be proud. Categories are gibberish to me. I understand-- it helps people organize their thoughts. But you can't go too far with it.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario