In front of a tangle of abstract sculpture in the corner booth of a deserted restaurant off the lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel, Fiona Apple is answering questions. It's a rainy day in April and really she's just talking.

She's told me she lives in Los Angeles, but she doesn't leave the house. Apple is 34 years old and doesn't have a driver's license. "I'm noticing now that I'm not feeling shame saying this," she says. "Whereas before I probably would've, like, lied a little bit about it and been like, 'Yeah, you know, I see friends sometimes.' But I really don't." She says when her phone rings with an invitation, she actually says, Oh, fuck! out loud, because then it's like, "I should go do this because if I don't, then that's really stupid. I'm gonna look like a crazy person." Apple says she's thinking about moving back east, but she's waiting for her dog to die first.

She's explained, unprompted, that she made 1996's Tidal, her harrowing, triple-platinum debut, because she was almost 20 and didn't have any friends and she wanted some.

Anyway, she's said all that, and now she's on to her anxiety about performing in front of people, which persists, though less than people imagine it to, to this day. "I used to have to pretend like I'd die if I saw anybody or if I met eyes with anybody in the audience," Apple says, but that's not true anymore, even though she giggles when I remind her that only a few weeks earlier she told an audience in Austin — one of a string of comeback shows in March, all rapturously received — "You're not real." (She does, however, seem comfortable enough around civilians, judging from a scene I witness right before the two of us sit down: Apple rushing up to a deeply perplexed man in a suit and enthusiastically introducing herself, mistaking him for me.)

And now she's telling me about her first psychiatrist, back when she was a kid, who showed her Rorschach blots and administered tests and wrote a two-page report about the whole thing that he and his colleagues gave to her parents. And Apple was furious, even then, about the things other people would write about her, because it was as if the doctors "didn't even see me — like, they got my hair color wrong even."

And she's about to tell me about her relationship with Jonathan Ames, the writer, whom she used to date but doesn't anymore, even though there is a song, "Jonathan," about him on her new record. Then she'll take a little bit more than seven long and not very articulate minutes to explain what the title of that new record, The Idler Wheel is wiser than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords will serve you more than Ropes will ever do (Epic), actually means.

But before she gets there, I am going to have to interrupt, because it's 2012, and Fiona Apple now has been doing this, trying to explain herself to strangers, for nearly 17 years. She's been a public figure for half her natural life. And she is still impossibly bad at it.

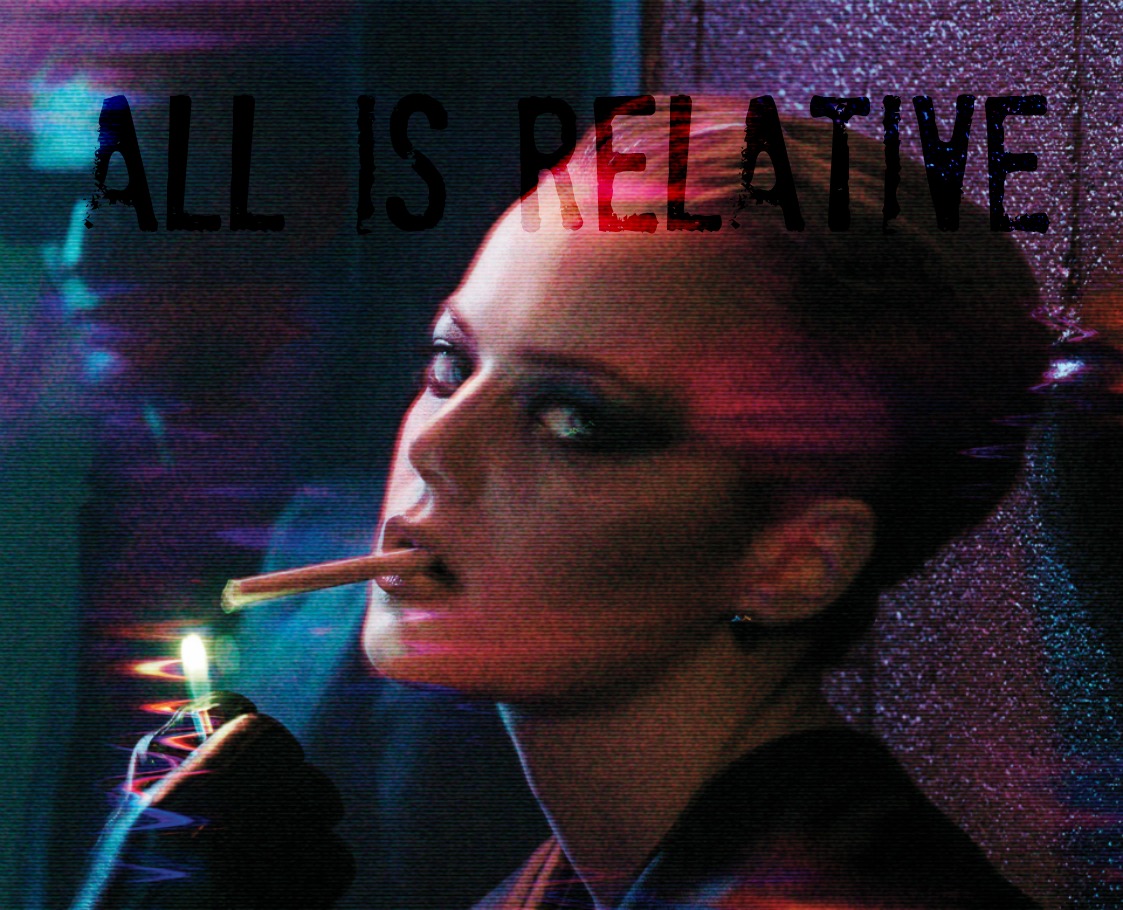

Let's begin with, well, SPIN. November 1997. "The Girl Issue." Fiona Apple's face is on the cover. "She's Been a Bad, Bad Girl," reads the cover line. Photographed by rutting porn auteur Terry Richardson — Apple choking herself, burrowing under some orange-red couch cushions. "Give me sexy, seduce me," Richardson says to her. Apple tells the writer, John Weir: "If you want to see me cry, just come to a photo shoot."

The article is redolent of the '90s. It contains this sentence: "A backstage pass hung from her navel ring." Apple's boyfriend at the time, a 24-year-old named David Blaine, is described as "the downtown New York card-tricks fixture." Apple calls her future Lilith tour-mate Tori Amos "a poster girl for rape," whatever that means. She tells Weir she's "going to help some little girl out there," and then, once that girl is saved by knowing that Fiona is human, and has bunions, "I'm going to die."

Apple ends up being so hurt by the way she's portrayed in the piece that she writes a 90-word poem about the experience and uses it as the title for her platinum second album, When the Pawn…, the length of which briefly lands her a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records.

But she doesn't stop talking to journalists. She doesn't even stop talking to SPIN. "I love her I-don't-give-a-fuck attitude," says Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott, in a February 2000 follow-up profile, titled "The Miseducation of Fiona Apple." In between, Apple does a Rolling Stone interview in which she talks about being raped at the age of 12 and gives the writer, Chris Heath, the name and current phone number of the Rollerblading teenage boyfriend who broke her heart and inspired many of the songs that ended up on Tidal.

"I did?!" She's staring at me incredulously.

Yeah. He proceeds to call, and there are quotes from the guy in the feature. And I'm looking at that, and I'm like, "Why would you ever give…"

"Wow. I don't even remember who I gave the number to, whose number it was, or why I would do that."

You just seemed really unguarded. You didn't need to give the journalist the number of that guy, but you did.

"I didn't need to, but it doesn't sound that crazy. Because the only thing that I'd have to be afraid of is whatever that ex-boyfriend would say about me. And if I'm being honest, I don't think I have an ex-boyfriend who would have something mean to say about me. I think that I probably knew that it would be okay."

We talk for a little while about this, the idea that a person in her position might choose to hold back as many details of her personal life as she could. That she spent the first five years of her career speaking her mind in public and being criticized for it. That many people who have sold far fewer records than she has might have figured out ways to be savvy and self-protecting around people who don't necessarily have their best interests at heart.

"How would I be more savvy right now?" she asks. She's genuinely perplexed. The failing light from the window outside is putting huge shadows around her huge eyes. Her hair is dyed red, and it's brushing her shoulders. She's wearing a camouflage green tank top and a long skirt and boots. And but for the fact that she looks like an adult now, and not a walking indictment of an industry that happily put a scantily dressed teenager on the cover of more magazines than she cares to remember, you could be talking to the same 19-year-old of all those years ago.

"Would I redirect the conversation? Or just talk about" — you can hear the disdainful quotation marks — "the 'new track' coming up? What do you do, except answer the questions honestly? What's the point if you're not going to? What's the point of any of this?"

As it happens, the new track "Every Single Night," the first single from Idler Wheel(which is great, by the way, stripped-down and savage and full of pointillist little stories and jagged, sticky images; it's maybe the best, or at least most complete, thing she's ever done), premieres on the Internet just a few hours before we sit down. Apple has no idea that the song is in the world until I mention it an hour later, when we're saying our goodbyes.

It's almost hard to remember now, in the age of Kanye and Gaga, how fame used to be something we foisted onto our unwilling pop stars. How so many of our idols from the '90s were so deeply uncomfortable with the spotlight. Kurt and Courtney and so on — all these people we basically ruined with our love. Fiona Apple is in many ways the last member of that unhappy elect, someone we brought screaming into platinum sales, who experienced the absolute worst the degenerate record executives and magazine editors were capable of, who was told by Terry Richardson at age 20: Give me sexy, seduce me.

The "Criminal" video, from 1997, is the thing you show children to explain to them why they shouldn't go into the music industry. It's the video that invented American Apparel advertising — Apple, skinny and cringing in her underwear, watching helplessly as her sneering anthem of louche indifference is transformed by Viacom and her label's minions into a plea for help.

That same year, MTV gave her a Video Music Award, which she accepted by saying: "This world is bullshit. And you shouldn't model your life — wait a second — you shouldn't model your life about what you think we think is cool and what we're wearing and what we're saying and everything. Go with yourself." From the stage she told her mother, "I'm so glad we're becoming friends," and then told the audience, "It's just stupid that I'm in this world."

All reasonable sentiments, except for perhaps the last one, but she was widely mocked for expressing them on national television. Three years later, on February 29, 2000, she was playing a show at New York's Roseland Ballroom, something went wrong with the sound, and she stormed off the stage in tears. Even now, 12 years later, she's still living this stuff down — still answering questions about those days. (For the record: "It wasn't fun to have a meltdown and stop a show. I mean, that would make me cringe for years. But I don't want to take it back now, because I sit here and it's funny to me. I'll talk about Roseland forever. I could talk about the speech I made at the Video Music Awards. All the things that would be embarrassing or something, I'm fine with it. I have no shame about any of that stuff. And it delights me to look at that, to be like, 'Look, you thought that was the end of the world." And it's not, it wasn't, it really wasn't, so much so that I have not a bit of cringe in me about these things.")

In the years since, she says, she's grown up — that's kind of what Idler Wheel is about. She hasn't worked much in the past decade. There was 2005's

Extraordinary Machine, with its own attendant controversy that boiled down to the swap of one producer, pop maximalist Jon Brion, for another, Dr. Dre confederate Mike Elizondo. While she was sorting that out, and rerecording the LP with Elizondo, fans started a misapprehending "Free Fiona" campaign — they thought her label was delaying the record — that nevertheless shows you how fiercely attached and protective her audience had become, even then. And now, on June 19, she'll release Idler Wheel, only her fourth LP in 16 years, and probably the first of her career to emerge without incident or strife or even much in the way of expectations.

"I sometimes think that I must time-travel and I don't remember it," Apple says, when I ask her what she does with all the time she spends not working. "Like, I must be off climbing a mountain in a parallel universe. I can't remember writing any of the songs that I've written. I don't know what the hell I do with myself. I feel like I'm 100 years old. I can't tell you what I did today. I can't tell you what I did for seven years. I can't tell you. It happens so seamlessly — I'm just floating along and seven years go by."

You can't remember writing any of your songs?

"No, I don't remember writing any of the songs."

According to Apple, the concept behind the title The Idler Wheel is wiser than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords will serve you more than Ropes will ever do is hard to explain but has to do with the idea of "being still in the middle of everything else but being able to feel everything." The idler wheel is the gear that does no work, drives no shafts. "It doesn't look like it's doing anything, but I feel like it's connected to everything," she says. It's about how she feels inside the machine of her own life and career. It's about how she marks time.

She read about whipping cords, which are used to bind and repair frayed ropes, in "this book about boating that was at my last boyfriend's house." The idea is less about avoiding mistakes than learning how to cope with them. "You're gonna get punched and blown around," she says. She looks over my shoulder into the empty restaurant, tries to figure out how to express what she wants to express. "What's valuable is to know how to make something out of that." Apple has had a lot of years to learn.

She made Idler Wheel over a few scattered months in 2009 and 2010 with her touring drummer, Charley Drayton, producing. According to Apple, her label only found out she was working on a new album when she handed it in early this year. Epic executives asked, in the way that executives do, if she thought the record was really finished — if there wasn't another song, a hit perhaps, still forthcoming. She told them it was finished, that it had to be finished, that the same week she'd finished it she'd broken up with her boyfriend, Jonathan Ames.

She'd thought: "I just finished writing an album. I can't write an album about you now, about breaking up." So instead he got a love song, "Jonathan." She tells me, pointing up toward her hotel room, that she'd been on the phone with Ames right before she came downstairs to meet me, and that they're still friends. For a while, she was going to leave the song off the record. She called him and said, "Listen, it's just a practical thing, because if I get another boyfriend, I don't want to have to deal with, 'Who's this Jonathan guy?' I honestly felt like it's just going to be the fight that breaks up my next relationship, and it's not worth it. But then I was like, 'Ah, fuck it.'"

"Jonathan" is one of only two unequivocal love songs on Idler Wheel. The other, "Anything We Want," might be the most romantic song Apple has ever written. "I looked like a neon zebra shaking rain off her stripes," she chants, or rather growls, intoning the lyrics as much as she is singing them. "And the rivulets had you riveted to the places I wanted you to kiss me." It's a very Fiona Apple metaphor, delicate and weird and somehow heartbreaking, and a welcome moment of relief in an album that's mostly about figuring out ways to let go of old loves and old lives.

"I stand no chance of growing up," she sings on "Valentine." But Idler Wheel is the most grown-up album she's ever made. According to Drayton, there isn't a single electric instrument on it: The entire recording is acoustic. You can hear Apple's newfound clarity, her resignation, her paradoxical optimism. "Nothing wrong when a song ends in a minor key," she sings on "Werewolf." And a couple times, as on "Daredevil" or "Regret," she screams, a full-body scream, over almost as soon as it begins. It is the sound of one world ending and another one right behind it, beginning again.

One advantage, she says, to making four albums in 16 years is that they become like autobiography, each record dividing one phase of life from the next. She says she hated working on Tidal. She spent those sessions doing crosswords under the piano in the Sony building in Manhattan. "I felt ridiculous being in a studio with real musicians, and I felt like everybody hated me. Everybody did hate me."

When the Pawn…, her second album, went better. "I was more in control, and I felt like I could do what I wanted to do, which is probably a good influence of Paul [Thomas Anderson, director of Boogie Nights and There Will Be Blood], who I was with then, because he is — in the best way — cocky. And I think that rubbed off on me. Like 'Yeah, of course I can do whatever I want.' "

Extraordinary Machine was cool, but she regrets the way she shoved Jon Brion off the project, though they're still friends, and he's apparently never mentioned it.

And then there's Idler Wheel. "This one I love, even though there's a lot of pain that I went through during the making of it. I feel very sure of myself. Not that I'm so great, but that I'm right. Nobody can tell me that my song isn't done," she says.

She looks up at the writer in front of her.

"Whatever I read in the paper, if somebody says that I'm crazy now? I'm not going to believe it just because they say it."